Do you understand?

The movement to eliminate ‘gobbledygook’ from government regulations and documents

Key points

- Plain language advocates say plainly written government materials can lead to savings in money, time and even lives.

- Part of the reason it can be challenging for federal agencies to use plain language is the wide audience they have to reach.

- Regulatory agencies could save time spent writing guidance documents for rules if the rule was written clearly in the first place, advocates say.

Anyone who has sifted through a 200-plus-page federal regulation probably comes away with the same insight: government documents can, at times, be confusing.

“Whether you like or loathe government regulations, I think everyone can agree that when one exists, it should be written as clearly as possible,” Rep. Bruce Braley (D-IA) said in a recent statement. “Sadly, gobbledygook dominates the regulations issued by government agencies, making it almost impossible for small businesses to understand the rules of the road.”

Braley is part of a growing movement to rid government regulations and other documents of confusing language. Instead, proponents of “plain language” call for government materials to be written in a simple, clear and easily understood manner.

Plain language advocates have achieved victories in recent years with the passage of the Plain Writing Act of 2010 – Braley-sponsored legislation requiring government agencies to write most documents in plain language. Government regulations are the exception to this law, but a recently introduced bill by Braley would extend the act’s requirements to any new or revised regulation issued by federal agencies.

As many advocates attest, plainly written and understandable government materials could lead to savings in money, time and – in the case of occupational safety and health-related documents – lives.

“It has a tremendous impact on safety,” said Don Byrne, the former head regulatory attorney at the Federal Aviation Administration. “If you’re trying to reach a large audience and raise the way in which they act in a safe manner, then you need to communicate with them and make sure they understand. Plain language definitely has that advantage.”

What is plain language?

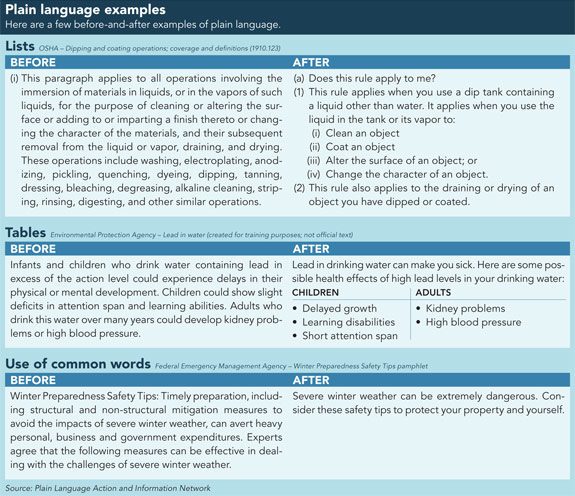

Simply put, plain language is communication written to an audience that can be understood the first time it is read, according to the Plain Language Action and Information Network, a volunteer organization of federal government employees supporting clear communication in government writing.

For advocates of plain language, clearly written regulations are a vital piece of the compliance puzzle for employers. “If they don’t understand and they go out and buy the wrong hard hat or put in place the wrong safety procedures, then you’re going to get injuries,” said Amy Bunk, PLAIN co-chair. “It could have been easily avoided if [the regulation] had just been written a little clearly.”

Bunk, who also serves as director of legal affairs and policy for the Office of the Federal Register in the National Archives and Records Administration, has seen a lot of government documents. Part of the reason it can be challenging for federal agencies to use plain language is the wide audience they have to reach, she said.

For example, if OSHA issues a document dealing with a particular hazard, that hazard could exist across several industries. Various people in those industries might have different skill levels, making it difficult for every single audience to understand OSHA’s message.

In such a situation, the documents should be written not for multiple audiences, but for the audience with the least amount of expertise, according to Annetta Cheek, chair of the Center for Plain Language, a Falls Church, VA-based nonprofit organization that wants the government and businesses to issue clear and understandable documents.

A former federal government employee and one of the founding members of PLAIN, Cheek stressed that plain language is not material written so anyone can read it; rather, it is written for the people who need to read and understand it. “Regulations are aimed at all sorts of different audiences,” she said. “Whatever that audience is should be able to read that document.”

Plain language in action

The technique of writing material for the audience that needs to understand it is missing from many old OSHA regulations, according to Charles Jeffress, who served as OSHA administrator from November 1997 to January 2001.

Currently chief operating officer at the American Association for Justice, a Washington-based attorney organization, Jeffress headed OSHA when it produced some of the agency’s first plain language documents from the Clinton administration. One such document was a standard covering dipping and coating operations, spurred by a 1998 presidential memorandum.

The problem with current OSHA regulations, according to Jeffress, is that the majority were adopted in the 1970s and came directly from consensus standards, such as those from the American National Standards Institute. Many of those standards were written by professionals in a specific field for other professionals in that field, not for the “everyman,” he said.

“When it comes to regulations, it’s the small business owner who’s running a machine shop who has to figure it out, and the industrial hygienist language may not be clear or understood by that person,” Jeffress said.

Employers are not entirely on their own, however. Many regulatory agencies routinely issue guidance documents to assist employers in complying with rules, and OSHA is no different. In fiscal year 2011, the agency issued 24 guidance or informational materials, with 20 expected to be released in both FY 2012 and FY 2013.

But as plain language advocates point out, those documents might not even be necessary if the standards were written more clearly. The result is an agency spending resources to produce two documents – the regulation and guidance for the regulation – when one may have sufficed.

“Why should you need those separate opinions telling people what the regulation says?” Cheek said. “You should just write the regulations clearly in the first place.”

Byrne noted that he has read studies by different agencies that have shown reductions in the number of people calling in with questions – and thus the number of staff needed to take those queries – by improving the language in regulations or the agency’s correspondence with the public.

Jeffress agreed, in theory, that if regulations were written more clearly there would be no questions. However, because OSHA regulations can apply to a broad range of industries and business types, some employers will apply the standard in an unforeseen manner, he said, making it necessary for some guidance documents or standard interpretations to be issued.

Government requirements

Federal agencies were required to fully comply with the Plain Writing Act by Oct. 13, 2011. Among the requirements:

- Write all new or substantially revised government documents in plain language.

- Designate a senior official to oversee the agency’s implementation of the act.

- Create a plain writing section on the agency’s website.

- Issue a final report by April 13, 2012, and annually every year after, outlining the agency’s compliance with the law.

Additionally, agencies are required to follow a plain writing guidance document published by the White House’s Office of Management and Budget. Regulations are exempt from the law, but the OMB guidance singles out the rule’s preamble – which serves as an introduction to a standard and outlines its purpose – and requires that section to be written in plain language.

President Barack Obama issued an Executive Order on Jan. 18, 2011, requiring government regulations be written in plain language and be easy to understand. The order is a supplement to an Executive Order from President Bill Clinton calling for all information provided to the public to be written in “plain, understandable language.”

Enforcement of such requirements can be difficult, however. Indeed, executive orders from one president can be rescinded by another, as when President Ronald Reagan rescinded an order issued by President Jimmy Carter that required a regulation to be written in “plain English.”

When Safety+Health contacted the Department of Labor to ask what policies – if any – it has regarding plain language in regulations, a DOL spokesperson referred the magazine to the department’s plain language website and to the specific safety agencies under DOL.

A Mine Safety and Health Administration spokesperson said MSHA has no set policy regarding plain language in regulations, and could not provide an accounting of any efforts the agency may be undertaking to ensure regulations are readable and understandable. An OSHA spokesperson did not respond to inquiries by deadline.

Until the Plain Writing Act, no enforcement mechanism had been in place to ensure agencies comply with plain language orders, Bunk said.

In addition to the new law requiring annual reports on agency compliance, it requires the public be given contact information and encourages them to reach out to agencies if they have trouble understanding documents, offering a type of public oversight. Bunk believes agencies will receive positive feedback on plain language efforts and begin to see the benefit of plain language.

Before retiring from the federal government in 2007, Cheek was brought into the Federal Aviation Administration following a survey among pilots who gave the agency low grades regarding the understandability of regulations and how they contribute to safety. From a focus group, Cheek, who was the FAA Language Program coordinator at the time, recalled pilots using words such as “dreadful” and “Byzantine” to describe FAA regulations.

As a result, two new FAA procedural regulations were written in plain language. Since that time, Cheek has noticed FAA regulations improving. While not always following every tenet of plain language, she said the agency has been using fewer passive verbs, shorter sentences and refraining from using the word “shall” as often – all of which contribute to a document being easier to read.

“Hopefully there’ll be a big plain language push in the health and safety area,” Bunk said, suggesting the requirements in the Plain Writing Act will get government agencies to be more open about using plain language in regulations. If not, Braley’s recently introduced Plain Regulations Act (H.R. 3786) would force them to do so.

“Unfortunately, it sometimes takes a law,” Bunk said.

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)